The Manhattan Bridge

February 12, 2013

[caption id="attachment_2150" align="alignleft" width="225" caption="Entry to the Manhattan Bridge pedestrian walkway. Photo by Jim Henderson."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_2150" align="alignleft" width="225" caption="Entry to the Manhattan Bridge pedestrian walkway. Photo by Jim Henderson."][/caption]

Yesterday, I decided to run home from work, a distance of about 4 miles from my office in Soho to my apartment in Brooklyn. The obvious crossing from Manhattan to Brooklyn is the Brooklyn Bridge, a beautiful span built in the 19th century that is easy to walk along. However, you can also cross the river via the far less popular Manhattan Bridge, which opened in 1909 and puts you pretty much in the same spot in Brooklyn as the Brooklyn Bridge does. I had actually never been on the Manhattan Bridge so this seemed like a good opportunity to try it out.

Unfortunately, since I’d never been on the bridge before, I did not have a good sense of where to get on it, on the Manhattan side. And, I didn’t realize this. I’ve always perceived my ability to navigate as being far better than it actually proves to be.

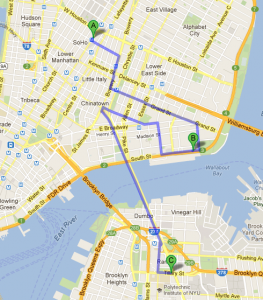

[caption id="attachment_2153" align="alignleft" width="263" caption="An accidental detour to Point B."][/caption]

[caption id="attachment_2153" align="alignleft" width="263" caption="An accidental detour to Point B."][/caption]

So, I took off running from my office. It was dark and cold last night, and my glasses kept fogging up, making it impossible to see. I also, as it turned out, had no idea where I was going so ended up overshooting the entrance to the bridge by about half a mile (point B on the map). In the process of getting lost, I had also been running along unlit, deserted paths, many of which had deep puddles full of icy slush.

Eventually, I made it to the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge. There is a reason why it is so unpopular. You aren’t running along charming, wooden footpaths, elevated above traffic. Instead, you run along concrete paths, enclosed by chain-link fencing, just a few feet away from an active subway line. And the Manhattan Bridge is lonely. Along its mile-plus span, I saw a total of maybe 5 or 6 people. I don’t know what the Brooklyn Bridge looks like at 7PM on a weekday in particular, but usually it’s filled with strolling tourists.

You also can’t get off the Manhattan Bridge easily. The Brooklyn Bridge has stairways about a quarter-mile from each end, since it’s designed for strolling. But once you’re on the Manhattan Bridge, you’re on it to the end, pretty much. As it turned out, this was OK since the Manhattan bridge goes mostly south, towards my house. But because of my poor sense of direction, I thought I was running east, well beyond my intended route.

Getting off the bridge, you have to cross several lanes of traffic with a barely-visible crosswalk and an inconspicuously-placed stop sign, with large trucks and buses rumbling by. Frustrated, wet, and cold, and thinking I was far away from my intended route, I jumped into a cab as soon as I crossed the boulevard, and asked the cabbie to take me home.

The question I was asking myself during most of my run was: what am I doing here? I think of myself as a fairly smart person and yet I was running along unknown paths, lost, seemingly far from where I wanted to be. I have this feeling from time to time. I’ve been stranded in a small village in Uganda, trying to get to another tiny village to begin a mapping project, and waiting four hours for someone who could get me there. I’ve finished grad school without a job and without any particular plan or direction that would allow me to move my career forward and pay back my loans. At these times I’ve felt lost and very, very uncomfortable, just as I did when I hailed that cab.

I sat down, relieved to be off my feet and headed in the right direction. Then I told the cabbie my home address. He immediately replied that he was actually heading back to Manhattan and so wasn’t willing to take me to an address in Brooklyn. (This is illegal, but happens sometimes.)

So, as quickly as I got in, I got out again. Not seeing any other cabs nearby, I started trudging in a random direction, looking for any familiar street. After a few minutes of frustration, I took out my phone to see how far the run home would be.

Not that far, as it turned out. And it also turned out that the bridge had been taking me in the right direction all along. So I started running again. The route was mostly downhill, and I got home less than fifteen minutes after I had decided to give up. But it is difficult to know that you are going in the right direction, when you’re doing something new. And it’s easy to assume that your feelings of being lost are the correct ones.